Louis Pasteur Swan Neck Flask

iii.1: Spontaneous Generation

- Page ID

- 23609

Skills to Develop

- Explain the theory of spontaneous generation and why people once accepted it as an explanation for the being of sure types of organisms

- Explicate how certain individuals (van Helmont, Redi, Needham, Spallanzani, and Pasteur) tried to prove or disprove spontaneous generation

Clinical Focus - Part 1

Barbara is a nineteen-year-quondam higher student living in the dormitory. In January, she came downward with a sore throat, headache, balmy fever, chills, and a violent but unproductive (i.e., no fungus) cough. To care for these symptoms, Barbara began taking an over-the-counter common cold medication, which did not seem to piece of work. In fact, over the side by side few days, while some of Barbara's symptoms began to resolve, her coughing and fever persisted, and she felt very tired and weak.

Practice \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What types of respiratory disease may exist responsible?

Humans have been asking for millennia: Where does new life come from? Organized religion, philosophy, and science have all wrestled with this question. One of the oldest explanations was the theory of spontaneous generation, which can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and was widely accepted through the Middle Ages.

The Theory of Spontaneous Generation

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) was ane of the earliest recorded scholars to articulate the theory of spontaneous generation, the notion that life tin can arise from nonliving matter. Aristotle proposed that life arose from nonliving cloth if the material independent pneuma ("vital estrus"). As evidence, he noted several instances of the appearance of animals from environments previously devoid of such animals, such as the seemingly sudden advent of fish in a new puddle of water.one

This theory persisted into the 17th century, when scientists undertook additional experimentation to back up or disprove it. By this fourth dimension, the proponents of the theory cited how frogs but seem to appear along the muddy banks of the Nile River in Egypt during the annual flooding. Others observed that mice simply appeared among grain stored in barns with thatched roofs. When the roof leaked and the grain molded, mice appeared. Jan Baptista van Helmont, a 17th century Flemish scientist, proposed that mice could arise from rags and wheat kernels left in an open up container for 3 weeks. In reality, such habitats provided ideal food sources and shelter for mouse populations to flourish.

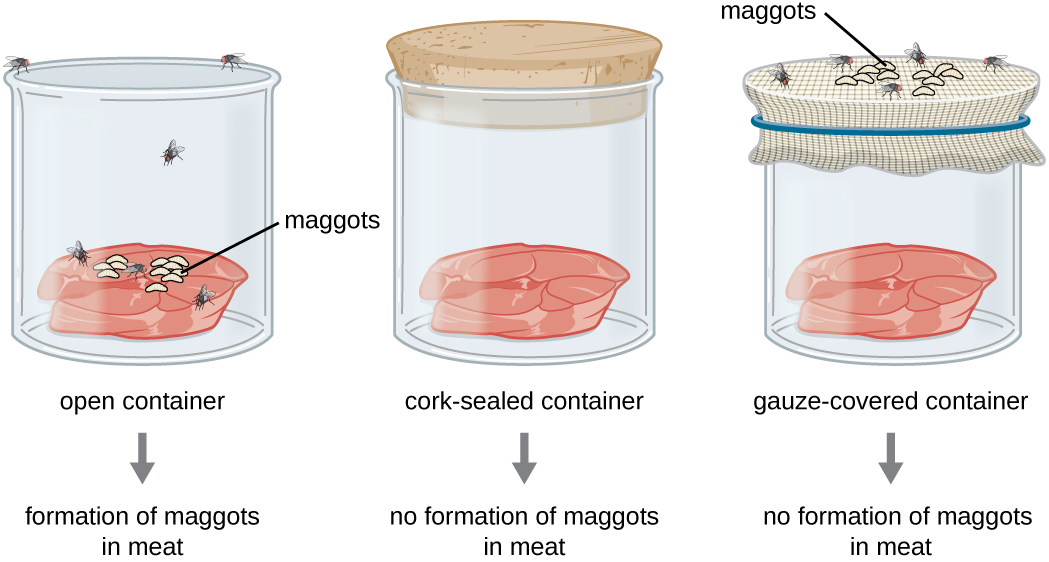

Yet, ane of van Helmont's contemporaries, Italian md Francesco Redi (1626–1697), performed an experiment in 1668 that was one of the get-go to refute the thought that maggots (the larvae of flies) spontaneously generate on meat left out in the open air. He predicted that preventing flies from having direct contact with the meat would too prevent the appearance of maggots. Redi left meat in each of six containers (Effigy \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Two were open up to the air, two were covered with gauze, and two were tightly sealed. His hypothesis was supported when maggots developed in the uncovered jars, but no maggots appeared in either the gauze-covered or the tightly sealed jars. He concluded that maggots could only grade when flies were allowed to lay eggs in the meat, and that the maggots were the offspring of flies, not the product of spontaneous generation.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Francesco Redi'southward experimental setup consisted of an open container, a container sealed with a cork top, and a container covered in mesh that let in air but non flies. Maggots only appeared on the meat in the open container. However, maggots were also found on the gauze of the gauze-covered container.

In 1745, John Needham (1713–1781) published a report of his own experiments, in which he briefly boiled broth infused with plant or animal matter, hoping to kill all preexisting microbes.2 He then sealed the flasks. After a few days, Needham observed that the broth had become cloudy and a single drop contained numerous microscopic creatures. He argued that the new microbes must have arisen spontaneously. In reality, nevertheless, he likely did not boil the goop enough to kill all preexisting microbes.

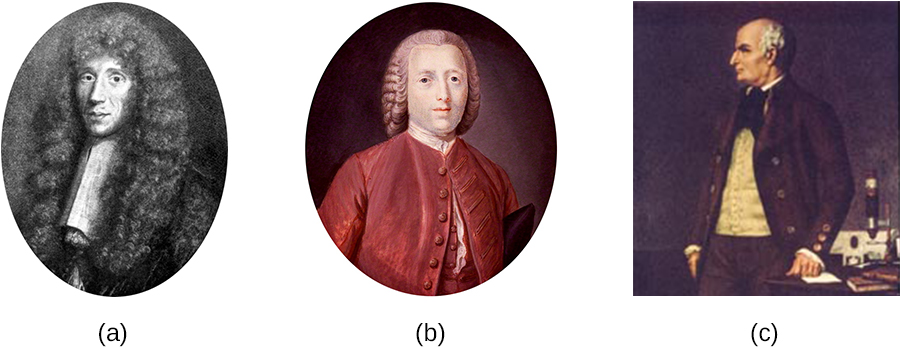

Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729–1799) did non agree with Needham'south conclusions, nevertheless, and performed hundreds of carefully executed experiments using heated goop.iii As in Needham's experiment, broth in sealed jars and unsealed jars was infused with plant and animal thing. Spallanzani's results contradicted the findings of Needham: Heated only sealed flasks remained clear, without any signs of spontaneous growth, unless the flasks were subsequently opened to the air. This suggested that microbes were introduced into these flasks from the air. In response to Spallanzani'south findings, Needham argued that life originates from a "life force" that was destroyed during Spallanzani's extended humid. Whatsoever subsequent sealing of the flasks then prevented new life force from entering and causing spontaneous generation (Effigy \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Effigy \(\PageIndex{2}\): (a) Francesco Redi, who demonstrated that maggots were the offspring of flies, not products of spontaneous generation. (b) John Needham, who argued that microbes arose spontaneously in broth from a "life forcefulness." (c) Lazzaro Spallanzani, whose experiments with goop aimed to disprove those of Needham.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

- Draw the theory of spontaneous generation and some of the arguments used to back up it.

- Explain how the experiments of Redi and Spallanzani challenged the theory of spontaneous generation.

Disproving Spontaneous Generation

The fence over spontaneous generation continued well into the 19th century, with scientists serving every bit proponents of both sides. To settle the debate, the Paris University of Sciences offered a prize for resolution of the problem. Louis Pasteur, a prominent French chemist who had been studying microbial fermentation and the causes of wine spoilage, accustomed the challenge. In 1858, Pasteur filtered air through a gun-cotton fiber filter and, upon microscopic exam of the cotton, institute it total of microorganisms, suggesting that the exposure of a broth to air was not introducing a "life forcefulness" to the broth but rather airborne microorganisms.

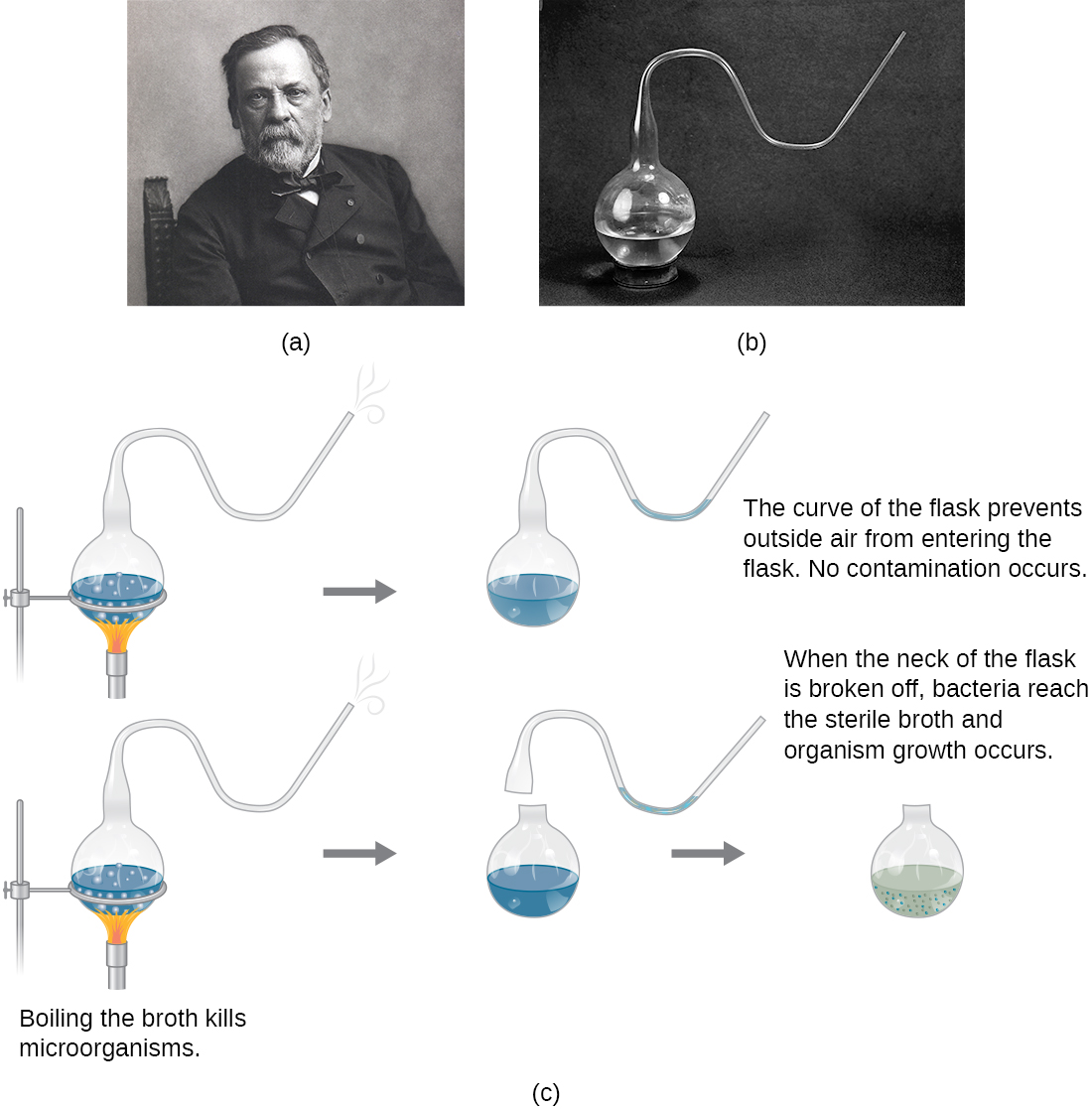

Afterwards, Pasteur made a series of flasks with long, twisted necks ("swan-cervix" flasks), in which he boiled broth to sterilize it (Figure \(\PageIndex{three}\)). His design allowed air inside the flasks to be exchanged with air from the exterior, merely prevented the introduction of whatever airborne microorganisms, which would get caught in the twists and bends of the flasks' necks. If a life forcefulness likewise the airborne microorganisms were responsible for microbial growth within the sterilized flasks, it would have access to the broth, whereas the microorganisms would non. He correctly predicted that sterilized broth in his swan-neck flasks would remain sterile every bit long as the swan necks remained intact. However, should the necks be broken, microorganisms would be introduced, contaminating the flasks and allowing microbial growth inside the broth.

Pasteur's set of experiments irrefutably disproved the theory of spontaneous generation and earned him the prestigious Alhumbert Prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1862. In a subsequent lecture in 1864, Pasteur articulated "Omne vivum ex vivo" ("Life only comes from life"). In this lecture, Pasteur recounted his famous swan-neck flask experiment, stating that "…life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this elementary experiment."4 To Pasteur's credit, it never has.

Effigy \(\PageIndex{3}\): (a) French scientist Louis Pasteur, who definitively refuted the long-disputed theory of spontaneous generation. (b) The unique swan-neck characteristic of the flasks used in Pasteur's experiment allowed air to enter the flask but prevented the entry of bacterial and fungal spores. (c) Pasteur's experiment consisted of 2 parts. In the first office, the broth in the flask was boiled to sterilize it. When this broth was cooled, it remained gratuitous of contamination. In the second part of the experiment, the flask was boiled and and then the cervix was broken off. The broth in this flask became contaminated. (credit b: modification of piece of work past "Wellcome Images"/Wikimedia Commons)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

- How did Pasteur's experimental pattern let air, but not microbes, to enter, and why was this important?

- What was the control group in Pasteur's experiment and what did it show?

Summary

- The theory of spontaneous generation states that life arose from nonliving thing. Information technology was a long-held conventionalities dating back to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks.

- Experimentation by Francesco Redi in the 17th century presented the first significant show refuting spontaneous generation by showing that flies must take access to meat for maggots to develop on the meat. Prominent scientists designed experiments and argued both in back up of (John Needham) and against (Lazzaro Spallanzani) spontaneous generation.

- Louis Pasteur is credited with conclusively disproving the theory of spontaneous generation with his famous swan-neck flask experiment. He afterward proposed that "life merely comes from life."

Footnotes

- ane K. Zwier. "Aristotle on Spontaneous Generation." http://world wide web.sju.edu/int/academics/cas...R.%20Zwier.pdf

- two E. Capanna. "Lazzaro Spallanzani: At the Roots of Mod Biological science." Journal of Experimental Zoology 285 no. 3 (1999):178–196.

- 3 R. Mancini, M. Nigro, Yard. Ippolito. "Lazzaro Spallanzani and His Refutation of the Theory of Spontaneous Generation." Le Infezioni in Medicina fifteen no. three (2007):199–206.

- iv R. Vallery-Radot. The Life of Pasteur, trans. R.Fifty. Devonshire. New York: McClure, Phillips and Co, 1902, one:142.

Contributor

-

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Marking Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern Land Academy), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian Chiliad. Forster (Saint Joseph's University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY four.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/i-introduction)

Louis Pasteur Swan Neck Flask,

Source: https://bio.libretexts.org/Courses/Portland_Community_College/Cascade_Microbiology/03%3A_The_Cell/3.1%3A_Spontaneous_Generation

Posted by: elliottcrial1955.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Louis Pasteur Swan Neck Flask"

Post a Comment